How to Save the Saviours

Deaths of doctors and nurses from COVID-19 in India and worldwide are of great concern. We need to draw the right lessons and make the healthcare system a safer place for medical workers…

By Dr Rajeev Jayadevan

By the very nature of their work, health workers are at increased risk to catch COVID-19. In the SARS outbreak of 2003, caused by a similar virus called SARS-Cov, one-fifth of the cases were healthcare workers. The novel coronavirus, also called SARS-Cov-2, is more contagious than its predecessor. Deaths from it occurred not only among older people, but also among those in the twenties and thirties. The deaths of Narjes Khanalizadeh, a 25-year-old nurse from Iran, and Dr Osama Riaz, the 26-year-old doctor from Pakistan are examples. British nurses Areema Nasreen and Aimee O’Rourke died in their thirties.

Systematic flaws contributing to doctors’ deaths

Infection in multiple healthcare workers can occur following surgery on a COVID-19 patient, as was documented following a hernia operation at the SMS Medical College Jaipur.

A large number of the infections that occurred among healthcare workers are from preventable factors. Being safe from the virus involves much more than wearing a mask and gown. Several administrative, academic and engineering measures are often overlooked.

Those who get infected with the virus need not always develop symptoms. Such people become a source of spread of virus to unsuspecting colleagues through repeated interactions in closed spaces. Such incidents have been reported in India and elsewhere. They may inadvertently spread disease to patients and bystanders. Hospitals have been a source of spread of Covid-19 in almost all countries.

When healthcare workers get sick, they either go into quarantine or get admitted to hospital. The total number of hospital beds are finite. The system gets stressed due to smaller remaining number of workers taking on greater volume of work. This workload includes the sick healthcare workers themselves as well as the patients whom they infected. This increases the infection risk among the remaining healthcare workers, setting off a vicious cycle.

When healthcare workers get sick, hospitals might get shut down, increasing the strain in the system. Healthcare workers cannot be replaced easily. It is not easy to train a new worker to do the same task.

Lessons learned from the healthcare workers’ deaths

Underestimating the pandemic

Being caught unawares is by far the biggest mistake that has happened to healthcare workers all over the world. That is, by realising late that the patient under their treatment had COVID-19. Often, a patient would get admitted with respiratory symptoms, and the diagnosis of the SARS-Cov2 virus would be made only several days later. By then, several healthcare workers and others would have become infected. A recent incident at NRS Medical College West Bengal highlighted this continuing problem.

The extent of local spread has been consistently underestimated in Spain, Italy, US and UK, resulting in a vicious cycle of healthcare workers getting infected and passing on to colleagues and patients. Although this might seem rather elementary, being in the habit of seeing patients without sufficient precautions is a major factor that caused infection, as can be seen from the cases of the departed. Healthcare workers at Singapore, on the other hand adhered to standard precautions and have had no outbreak among healthcare workers. Standard precautions are protective even if there is unexpected exposure to aerosol. In the present scenario, it is safer to treat every patient as COVID-19 till proven otherwise. Implementation of IPC (Infection control precautions) even after a delayed diagnosis has effectively prevented further spread of infection in such cases shows that following standard precautions at all times is an effective preventive tool.

Ignorance about the extent

In Italy, the pandemic arrived at the same time as the annual flu season. Reportedly, many GPs continued to see patients casually, thinking it was only a minor flu. Over 150 doctors have died in Italy alone from COVID-19. Ignorance about the extent of local spread contributed to deaths. In addition, some of the reported COVID deaths in healthcare workers could also be non-work related.

In Spain, doctors were not informed early of the extent of spread, hence did not take adequate precautions. In China, the early spread of COVID-19 to healthcare workers occurred because patients went to see doctors in local clinics who had no knowledge of such an outbreak, and saw these patients without precautions.

Asymptomatic spreaders

Many healthcare workers still believe that only sick-looking people could give them the virus. They remain unaware of the large segment of asymptomatic spreaders, and let their guard down while in the company of apparently healthy people.

Lack of testing facilities

Lack of testing facilities, denial and underreporting of the pandemic contributed to this ignorance among healthcare workers. Unfortunately, without widespread testing, it is impossible to contain the spread of the virus in a region. Several countries are still unable to test adequate numbers of their population due to multiple reasons.

Germany on the other hand, was proactive in preparing as early as January with testing facilities. Prof. Dr Christian Drosten and team, Institute of Virology, Hospital Charite of Berlin developed the PCR testing kit early, and immediately shared the technology with other labs.

Need for surveillance testing

Periodic surveillance of healthcare workers by testing is necessary to detect infected people early and to isolate them. As infection does not always result in symptoms, waiting for fever or cough to appear before testing is the wrong strategy in the healthcare worker setting. It must be noted that surveillance testing is different from diagnostic testing. Surveillance testing of healthcare workers during a pandemic is done to protect the hospital and the community—by identifying and isolating infected individuals early. Example of diagnostic testing is when it gets ordered for a patient who is admitted with severe pneumonia, where it is primarily for documentation of the diagnosis. The virus has already affected healthcare workers in major hospitals in India, while the status of the vast majority of other hospitals is still unknown because surveillance testing is not being done yet. When hospitals unknowingly start spreading the virus to visiting patients, the disease penetrates deeper into the community and the pandemic gets worse.

Shortage of PPEs

Shortage of PPEs has been blamed in all nations including US, Italy, Iran and UK. This requires customised solutions according to each nation’s circumstance and policy. Inappropriate and excessive use of PPE could also lead to wastage of resources, eventually causing shortage. Hence, judicious use of PPE must be promoted, according to scientific guidelines rather than by perceived risk or excessive fear of infection. Hoarding of precious resources such as N95 masks by those who don’t need it, must be discouraged. In Italy, the death of 67-year-old Dr Roberto Sello is said to have occurred after he continued to see patients after PPE ran out.

A large number of healthcare worker infections in Iran — up to 41% of the COVID-19 cases — are reportedly attributed to PPE shortage. Those healthcare workers taking care of sick relatives at home must be careful not to bring the virus to the workplace. If a family member is sick with fever, coming to work could be risky to colleagues—in the setting of a pandemic.

Right quarantine strategies

Self-quarantine (self-isolation) is an important aspect of prevention. It refers to keeping a potential virus carrier from infecting the healthy community around. Therefore, it applies to healthcare workers who had significant contact with a COVID-19 patient. The local protocols and the logic behind them must be repeatedly emphasised to all healthcare workers. However, overzealous quarantine strategies can lead to a depleted workforce. In Singapore and Hong Kong, quarantine is advised only for those who had close contact by definition, and they are able to preserve their healthcare worker workforce as a result.

Reverse quarantine must be practised where applicable. Reverse quarantine refers to protecting the vulnerable from others who might give them the disease. The COVID-19 related death of an 85-year-old doctor who had reportedly had pre-existing cardiac morbidity in Mumbai, soon after the visit of his grandson from the UK, highlights the need to reverse quarantine the elderly and vulnerable. Every effort must be made to prevent the entry of the virus into the households where such individuals are living. The report that other family members also tested positive suggests that the visitor’s earnest efforts at self-quarantine were not enough to stop the virus from infecting others in the household.

Infection control measures

Housekeeping, laundry and biomedical waste disposal departments play a major role in disinfection and prevention. They must be involved in infection control meetings. Guidelines for disinfection have been published. Diluted household bleach solution (1% Sodium hypochlorite) is effective for most non-metallic, non-fabric surfaces. It is economical and easily made by mixing two tablespoons of bleaching powder in one litre water.

Wrong use of PPE

Unauthorised reuse of PPE increases infection risk, and is an expected outcome of shortage. The death of Dr Frank Gabrin in New York is an example. CDC has published a new guideline on reuse of N95 mask during times of shortage. Wrong use of PPE is widespread among healthcare workers. Putting on and removing PPE requires special training. Mask and glove use are commonly done wrong. Substandard PPE has been implicated, as manufacturers cut corners to improve their profits. These errors can be easily remedied by supervision and training programmes.

Emergency intubation

Healthcare workers are often exposed to a high viral load in the casualty or ICU before standard PPE could be worn for emergency intubation procedures. Those who work in these settings must therefore anticipate being in such positions and take sufficient preparation.

Lack of IPC

Every hospital must have a strong and efficient Infection prevention and control (IPC) that decides local policy based on established guidelines, trains personnel and audits the outcome. Even in developed nations, compliance is never a 100%, hence the need for continuous monitoring. Longer working hours and fatigue contribute to risk of infection. The hospital administration must take these recommendations seriously. Lack of IPC has been blamed as a major factor in healthcare worker deaths.

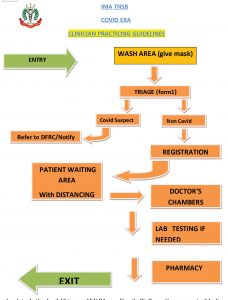

Efficient triage of patients before they reach the reception is an important step in reducing the spread of virus at the facility. Patients who are visiting can be counselled in advance of handwashing, sanitising, mask use and be provided a route map.

The flow of patients and staff through the hospital must be planned to minimise spread of infection. This can be achieved through administrative and engineering controls. Also called TCB or Traffic Control Bundling, such measures have effectively prevented healthcare worker infections at hospitals.

Cohorting of staff prevents the mingling of those who work in high risk areas with those who work in other parts of the hospital. This reduces risk of infecting colleagues. When procedures are done that are high risk for aerosol, the number of staff present in the room must be minimised. The air flow in such rooms must follow strict engineering controls.

Minimising risk from speech

Everyday speech has great role in transmitting the SARS-Cov-2 virus in the form of really tiny invisible droplets. In the April 15 issue of NEJM, Anfinrud et al from NIH have demonstrated how speech generates tiny droplets that are effectively blocked by wearing a cloth mask.

Taken together, these findings have significant role is devising preventive strategies. Limiting conversation in closed spaces, maintaining universal social distancing and asking all patients to wear a mask before entering the room or facility are simple, economical yet evidence-based measures that can be easily practised.

Wearing of masks has been a shifting topic. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India has asked the general public to wear mask while stepping out. Periodic multidisciplinary meetings with all stakeholders within a hospital will help make the place safer for everyone. Such meetings must involve those who work in engineering, maintenance, pharmacy, microbiology, lab, nursing, housekeeping, human resources, doctors and administration.

Avoiding asymptomatic transmission

In a study published by the CDC team in NEJM on April 24, the role of asymptomatic transmission as the Achilles heel of community spread of COVID-19 has been discussed. This means that healthcare workers could get infection from a well-looking colleague or patient or bystander simply through conversation.

Elderly doctors at threat

COVID-19 related mortality increases over age 65, and also among those with associated conditions such as diseases of the heart, lung, kidney and liver, cancer, obesity and diabetes. Healthcare workers who are over 65 or otherwise vulnerable may therefore be assigned to non-clinical areas of work, where the risk of contracting the virus is lower. Such measures will reduce overall healthcare workers’ mortality risk. A substantial number of doctors and nurses have died after coming back from retirement to serve on the frontlines. In France, Dr Jean-Jacques Razafindranazy, 67 came back after retirement to help the ER, and died of COVID-19. In Cardiff, Wales, 65-year old nurse Gareth Roberts had a similar fate. So was the case of Dr Alfa Saadu, 68, returned from retirement to help out at a local hospital in the UK.

Keep patients’ volume down

Doctors who see extraordinarily large volume of patients are exposed to greater viral loads. It is unclear whether repeated exposures lead to more severe infection. The death of 62-year-old Dr Shatrughan Panjwani of Indore, who dutifully saw patients from slum areas, raises the question of limiting patient numbers in clinics. Introducing engineering controls to promote social distancing, wearing of masks by all patients and bystanders, and improving natural ventilation in busy outpatient clinics are related topics. Infection control precautions are not easy to implement in such settings.

Ignorance is a killer

Underestimating the ignorance of individual healthcare workers is a mistake that happens to policy makers. It is commonly assumed that those at the grassroots level will completely understand, remember and carry out instructions. In reality, this does not happen. Besides, it is difficult to find out how many people did not understand instructions. Apart from an audit, there is no reliable method to measure the level of ignorance and non-compliance. For instance, even in well-equipped settings, faulty use of PPE is common, resulting in spread of infection. Being vigilant and taking proactive steps will help prevent complications that are a natural outcome of ignorance. Unfortunately, as a group, healthcare workers are at greatest risk when the prevailing level of ignorance is high.

Ignorance is not necessarily the fault of the healthcare worker. Faulty public health policies where health education as well as data collection are done without foresight can result in the collective blinding of entire communities.

Delay in recognising the community spread of the virus in Italy and Spain cost many healthcare workers their lives. Older doctors and nurses with chronic illnesses returning from retirement to serve on the frontline is not a model of ideal workforce deployment. Declaring an area to be safe without adequate testing is yet another example of collective ignorance; this can be dangerous to a large number of people.

In a pandemic, media play a major role in dispelling ignorance. Imposing penalty for fake news helps prevent misinformation, which is another contributor to ignorance. Methods of health education require substantial customisation for the population intended. Ignorance of policy-makers represents a larger problem, as has been documented in several nations.

Checklists to eliminate errors, pre procedural briefing, post procedural debriefing, team-based simulation and training are helpful in intensive care settings.

Lying patients

Patients are known to conceal their high-risk travel or contact history, and this has been implicated in the deaths of doctors. Hence, there is no substitute to taking standard precautions with all patients, however impractical it might seem.

Among all risk factors, ignorance appears to be the most dangerous as well as remediable from the viewpoint of a healthcare worker.

All healthcare workers are vulnerable

The risk applies not only to nurses and doctors, but also to pharmacists, technicians, physiotherapists, receptionists, paramedics, attenders, ambulance drivers and other staff. All healthcare workers therefore require training and protection according to their level of exposure to the virus. The deaths of 35-year old pharmacist Ismail Durmus in Turkey, 33-year-old UK pharmacist Pooja Sharma, 28-year-old Calire Marie Fuqua, a receptionist in a paediatrician’s office in Louisiana, US show that the virus does not discriminate by age, type of clinical work or gender. Infection of staff working in high traffic areas such as the pharmacy was documented at SMS Medical College Jaipur. Two young attenders Oscar King Jr and Elbert Rico, also known as porters in the UK, died at John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford.

Doctors working with the airway such as dentists, and anaesthesiologists are especially at risk for COVID-19 infection. In a study, this group comprised 12% of all doctor deaths from COVID-19. Psychiatrists make up 3% of deaths among doctors (6 deaths out of 198). This suggests the risk from prolonged exposure to aerosol by conversation in a closed environment.

GP/ER doctors make up 40% cases followed by 6% Medicine, 5% dentistry, 4% 6% Medicine, 5% dentistry, 4% Cardiology, 4% Ophthalmology, 4% ENT, 3% Respiratory, Cardiology, 4%, Ophthalmology, 4% ENT, 3% Respiratory, 3% Psychiatry3% Psychiatry, and , and 3% Anaesthesia, 3% Gen Surgery, 3%, Obstetrics/Gynaecology 3%, Anaesthesia 3%, and Gen Surgery, 3%.

With their hands-on experience with Covid-19, Mirco Nicoti et al from Italy are advising a massive deployment of outreach services. They assert that pandemic solutions are required for the entire population, not only for hospitals. Home care and mobile clinics may be used for less ill patients. These measures release pressure from hospitals, preserve PPE, beds, ventilators, decrease contagion, thus protecting patients and healthcare workers.

Mortality or CFR Case Fatality Rate of COVID-19 is not a fixed number. It depends on quality of care available. If healthcare systems are overwhelmed, the mortality increases up to five-fold. This directly applies to healthcare workers working in these areas. It is therefore important to take widespread measures for the entire population to preserve valuable resources, as discussed above. Recognising work-related stress and seeking help early is important.

Anyone who works in healthcare is at risk. In addition to doctors, nurses and other clinical staff, infection is also known to occur among non-clinical personnel within a health-care setting. Focus and terminology should therefore shift from “health-care workers” to “health workers”, thus encompassing drivers, cleaners, security guards, burial teams, community-based workers and all others who are at risk while performing health services. In the SARS 2003 epidemic, a study published in NEJM showed 136 patients being infected as a result of one patient admitted to ICU. The infection spread to 20 doctors, 34 nurses, 15 other health workers, 16 medical students and 53 patients who happened to be at the hospital at the same time, in spite of the use of PPE. Aerosol-generating procedure using a jet nebuliser was the likely cause of this spread.