Poor Air Quality: A Global Threat

The increasing level of poor air quality becomes a global warming and threat of emerging and re-emerging disease…

The increasing level of poor air quality becomes a global warming and threat of emerging and re-emerging disease…

By Dr Amitav Banerjee

Experts give short term solutions. Visionaries offer long term solutions. If we use their lenses we realize that many problems and their solutions are interrelated. We realize that technology without a blend of philosophy is sterile and often adds to the problems instead of solving them.

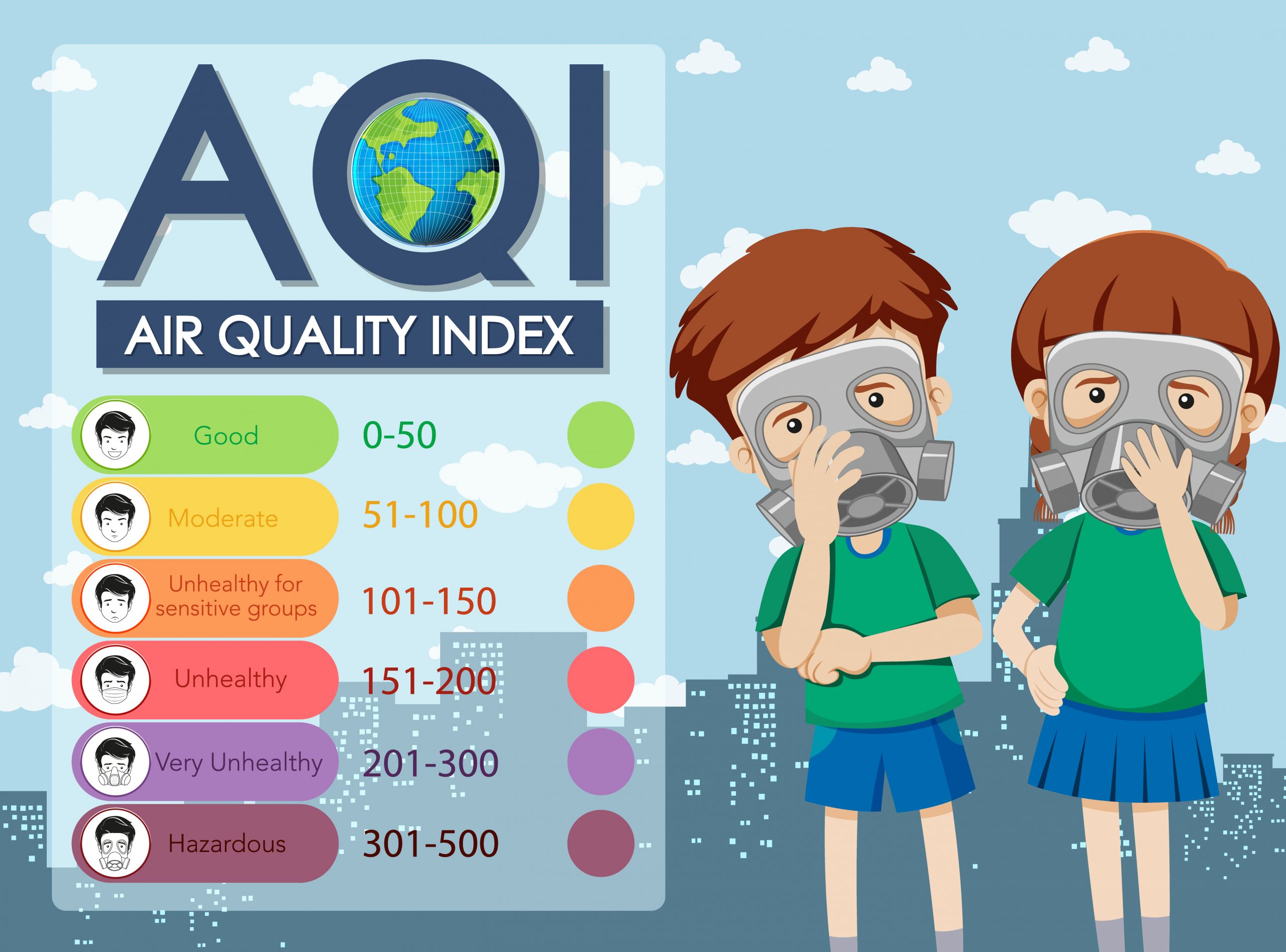

This narrative examines the hazards to human health due to deteriorating air quality in major cities in India, and short term and long term solutions. Every winter, heavy smog has become a regular feather in the national capital especially Delhi/NCR regions. Smog is a combination of smoke and fog entrapping particles in its fold. Besides being a health hazard, it seriously limits visibility often jeopardizing traffic movements and delaying flights.

A periodic phenomenon is the “Asian Brown Cloud,” that hovers over eastern China and South Asia, every year from November onwards. This is due to large amounts of aerosols composed of soot and dust as a result of combustion of fossil fuels and biomass over the region. The Asian Brown Cloud has been linked with decrease in summer rainfall in India, decrease in agricultural activities and increased industrialization. Initial observations of this phenomena were made in the late 1990’s as part of the Indian Ocean Experiment (INDOEX) which triangulated air pollution indicators estimated by satellites, aircrafts, ships, surface stations and balloons.

Since then air pollution has shown a rising trend particularly in Delhi. Only in the last decade civil society and media focused on the high PM 2.5 concentrations, which are more hazardous (Particulate Matter < 2.5 micrometer, particles larger than this are less hazardous as they are blocked and eliminated by the surface mucus and cilia of the respiratory system).

This year too, come November, Delhi was engulfed in heavy smog with poor air quality. School closure was recommended and debate around the root cause of the problem resurfaced. Both the events and the debates have become a pattern over the years. The issues are political, commercial, and last but not the least in conflict with the aspirations and lifestyles of the rapidly expanding middle class.

Civic Society and Supreme Court interventions

Civic society has been active. Pleas by activists about polluting industries and motor vehicles was admitted by the Supreme Court in 1995 and again in 1996, which adjudicated that Delhi was the fourth most polluted city in the world as measured by suspended particulate matter (SPM). The major contributors to pollution were vehicles and industries. The court directed over 13000 polluting industries and many brick kilns to relocate beyond the city limits. The court also recommended the setting up of the Environmental Pollution Control Authority (EPCA). This was created in 1998.

The EPCA recommended a two year action plan to convert all Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) bus fleet, taxis, and autos to Compressed Natural Gas (CNG), removal of leaded petrol and commercial vehicles more than 15 years old, and restricting the number of two stroke auto rickshaws. Coal based power plants were also asked to convert to gas-based.

Air Quality Standards Revised

In the year 2009, the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) were revisited to include 12 pollutants including PM 2.5. As mentioned while large particles can be ejected by natural defence mechanisms in the respiratory tract, particles smaller than 2.5 microns evade this defence and can penetrate deep in the lungs causing respiratory and cardiovascular problems and can affect other organs. The revised NAAQS recommends acceptable annual PM2.5 limit 40 micrograms per cubic meter as against the WHO standard of 5 micrograms per cubic meter.

During the winter of 2016, Delhi experienced one of the worst episodes of hazardous air quality with PM2.5 rising to over 900 microgram per cubic meter, many times higher than acceptable limits by whatever standards.

Monitoring and Surveillance of Air Quality

Established in 1982, the National Air Quality Standards are updated regularly. The National Air Quality Monitoring Programme (NAMP) estimates the ambient air quality and monitors compliance with standards. The National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) for Indian Cities was launched in 2019. It envisages surveillance and response of 122 polluting cities to ensure city-specific measures to reduce PM2.5 levels by 20-30 percent by 2024 taking 2017 as the baseline.

Other government schemes include BS-VI emission standards for motor vehicles, the National Electric Mobility Plan 2020, and accelerating LPG availability at household levels.

How much impact at population level?

The results of the measures have been disappointing. World Air Quality Report 2021 reveals that air pollution in India increased in 2021 with average PM2.5 levels 10 times the recommended levels. Among the 100 most populated cities in the world 63 Indian cities were included.

The reasons for this dismal impact are many. Poor funding for the various schemes, poor compliance in absence of legal deterrent and inadequate monitoring are some of the reasons. India had only 804 air quality monitors in 2021 or 0.14 monitors per million population. This compares poorly with China (1.24), US (3.4) and Brazil (1.8).

Cost of newer and cleaner technologies such as solar energy, wind energy, and storage batteries may have dropped appreciably, however financing and regulations have lagged behind. These need to be implemented at rapid pace.

National Hydrogen Mission – Green Hydrogen Policy

The National Hydrogen Mission was launched on India’s 75th Independence Day, 15 August 2021. The aim is to produce 5 million tonnes of green hydrogen by 2030 to enable renewable energy capability. The Government of India notified the Green Hydrogen Policy in Feb 2022 for implementation by concerned agencies.

Hydrogen and Ammonia are expected to replace fossil fuels in the future. These will be produced by using power from renewable energy sources.

Impact of Technology without vision will be limited.

While the above technological solutions hold promise to curb the escalating levels of air pollution, earlier experience should caution us of their limitations.

Major paradigm shifts are needed to address the air quality and associated issues such as global warming not only in India but across the globe. While Gandhi’s views on environment and the simple life may seem too idealistic to many, some of them can offer long term solutions.

Father of Nation Mahatma Gandhi had expressed his concerns about urbanization and mechanization and their impact on the environment, in his speeches and writings. “Hind Swaraj”, written by him more than a century ago, warned of the dangers of rapid unplanned urbanization which he said would be slow death for villages and villagers. Abolishing of cottage industries would remove the opportunities of employment in rural area and promote urban migration. He stressed on production by the rural masses instead of mass production in urban areas.

At the individual level a bit of Gandhism will not only check air pollution but will improve population health. Increasing cars on Indian roads not only leads to poor air quality but their overuse by the urban middle class predispose to obesity and related ills. Western populations are two to three times more obese that Asian and African populations. However, the urban middle class in India is fast catching up with their Western counterparts. Market forces promoting new cars on congested Indian roads, and junk food through Swiggy and Zomato to the sedentary urban middle class lead to poor quality of air we breathe and poor quality of food we eat.

Gustavo Petro, the former mayor of Bogota, once said, “A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It is where the rich use public transport.”

Fast developing economies like India should pause and introspect. Such economies generate a vast middle class with disposable incomes, an ideal target for market forces promoting automobiles and urban centres of mass production accelerating the environmental disaster. Mahatma Gandhi had rightly anticipated that the Earth has enough resources for our need but not for our greed.

Adopting the vision and lifestyle of the Mahatma, even partly, both by society and the people, will go a long way in solving the health hazards at the population level and preventing diseases at the individual level..

(The author is Clinical Epidemiologist, is currently Professor and Head, Community Medicine, Dr D Y Patil Medical College, Pune.)