Problem of Plus-Size

Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome (OHS), a risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea, is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.Treatment options include weight reduction, positive airway pressure therapy and surgical interventions including bariatric surgery …

By Dr Pranav Ish

OHS is defined as a combination of obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 30 kg/m2 ) with daytime hypercapnia (pCO2 > 45 mm Hg) in the absence of other known causes of alveolar hypoventilation.1 Such patients generally also have underlying sleep apnea.

PREVALANCE & BURDEN

Obesity is a risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS). Some studies have found hypercapnia in 10% to 20% of OSAHS patients; however, these studies were limited by small sample size, biased recruitment of patients with COPD or severe obesity, and the exclusive enrollment of one gender group and/or ethnic background. Hence, the exact prevalence of OHS is not known. Also, little is known about prevalence of OHS in the obese population, irrespective of OSAHS. Current estimates suggest that around 0.3% to 0.4% of the population may have OHS. Prevalence of OHS is set to increase with rising obesity; therefore, accurate assessment of prevalence of OHS is critical for planning health services to make provision for this condition.

Furthermore, the need for early detection of OHS is clear because delay in diagnosis and treatment is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. If left untreated, OHS is associated with a mortality of 23% at 18 months following discharge from hospital; adequate treatment of OHS reduces this to 3%. In addition, untreated OHS patients are likely to require invasive mechanical ventilation with longer hospital stay.

The standard assessment to screen for daytime hypercapnia is measurement of arterial blood gases. It has been suggested that obese patients with hypercapnia have higher BMI, more severe OSAHS, and worse restrictive chest wall mechanics, and a higher chronic bicarbonate levels than normocapnic obese patients.

PATHOLOGY & TREATMENT

The pathophysiology of OHS is complex, more like a vicious cycle. But effective treatment options are available which block this complex pathophysiological pathway at different levels.

The root cause is obesity, so treatment for that is most effective, directly inhibiting all further pathways. Pure obesity with OSA leading to OHS without leptin resistance is a pathway, which if diagnosed and treated early, can help in effective cure.

Weight reductions by diet control, exercise and surgical options like bariatric surgery have shown to be highly beneficial. Positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy has been the cornerstone of treatment. Continuous PAP therapy works in most patients; few may require bi-level PAP therapy. Drugs like medroxy progesterone and acetazolamide as respiratory stimulants have unproven role.

Thus, the modern era of obesity unfolds new burdens of undermined diseases for which early diagnosis, treatment and more so, prevention is the key to prevent further morbidity and mortality.

Types of Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric surgery includes a variety of procedures performed on people who have obesity. Weight loss is achieved by reducing the size of the stomach with a gastric band or through removal of a portion of the stomach or by resecting and re-routing the small intestine to a small stomach pouch.

The type of surgery that may be best to help a person lose weight depends on a number of factors. In open bariatric surgery, surgeons make a single, large cut in the abdomen. More often, surgeons now use laparoscopic surgery, in which they make several small cuts and insert thin surgical tools through the cuts. Surgeons also insert a small scope attached to a camera that projects images onto a video monitor. Laparoscopic surgery has fewer risks than open surgery and may cause less pain and scarring than open surgery. Laparoscopic surgery also may lead to a faster recovery.

Open surgery may be a better option for certain people. If you have a high level of obesity, have had stomach surgery before, or have other complex medical problems, you may need open surgery.

There are the surgical options like laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, gastric sleeve surgery, also called sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass. Surgeons also use a fourth operation, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, less often.

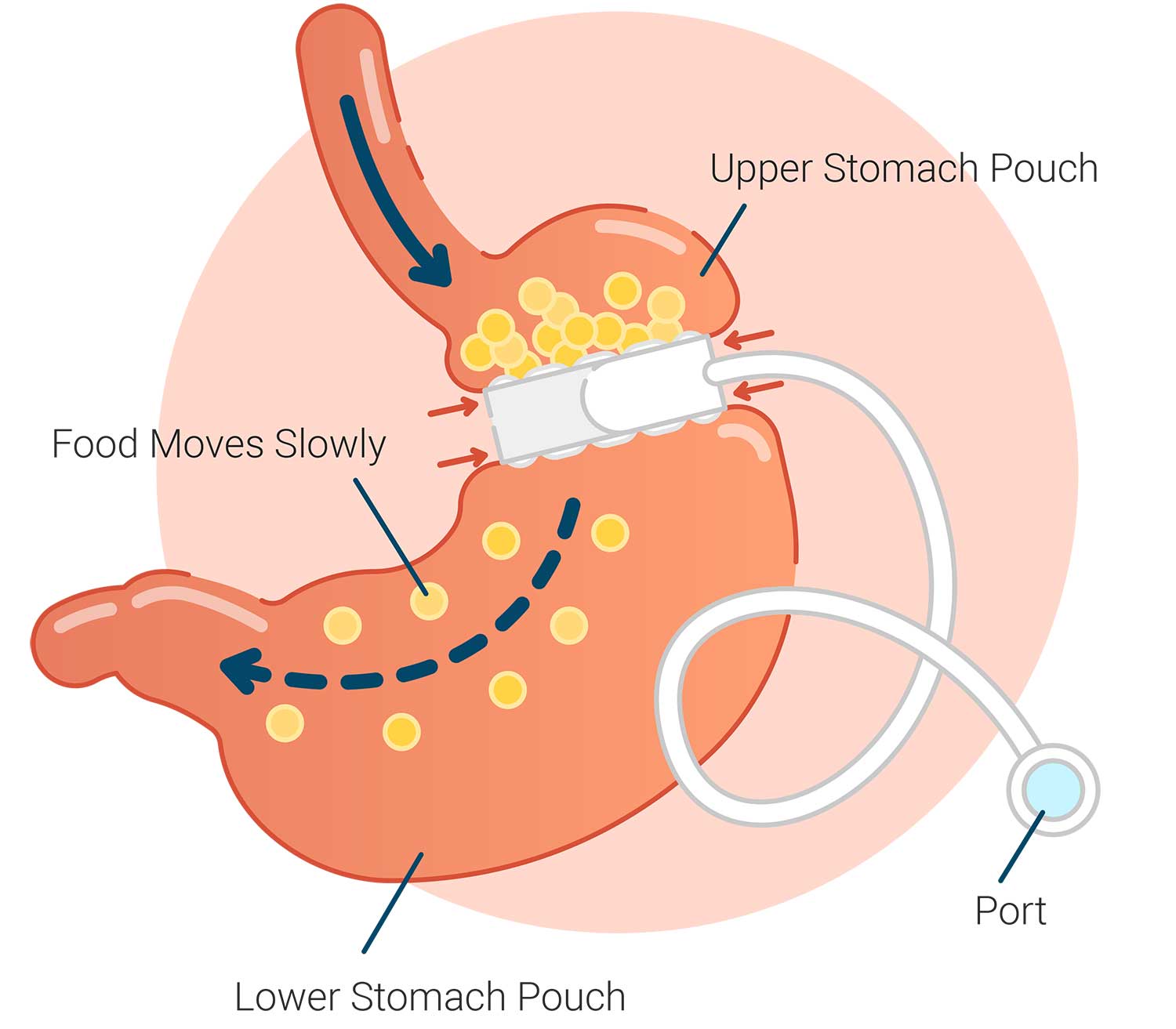

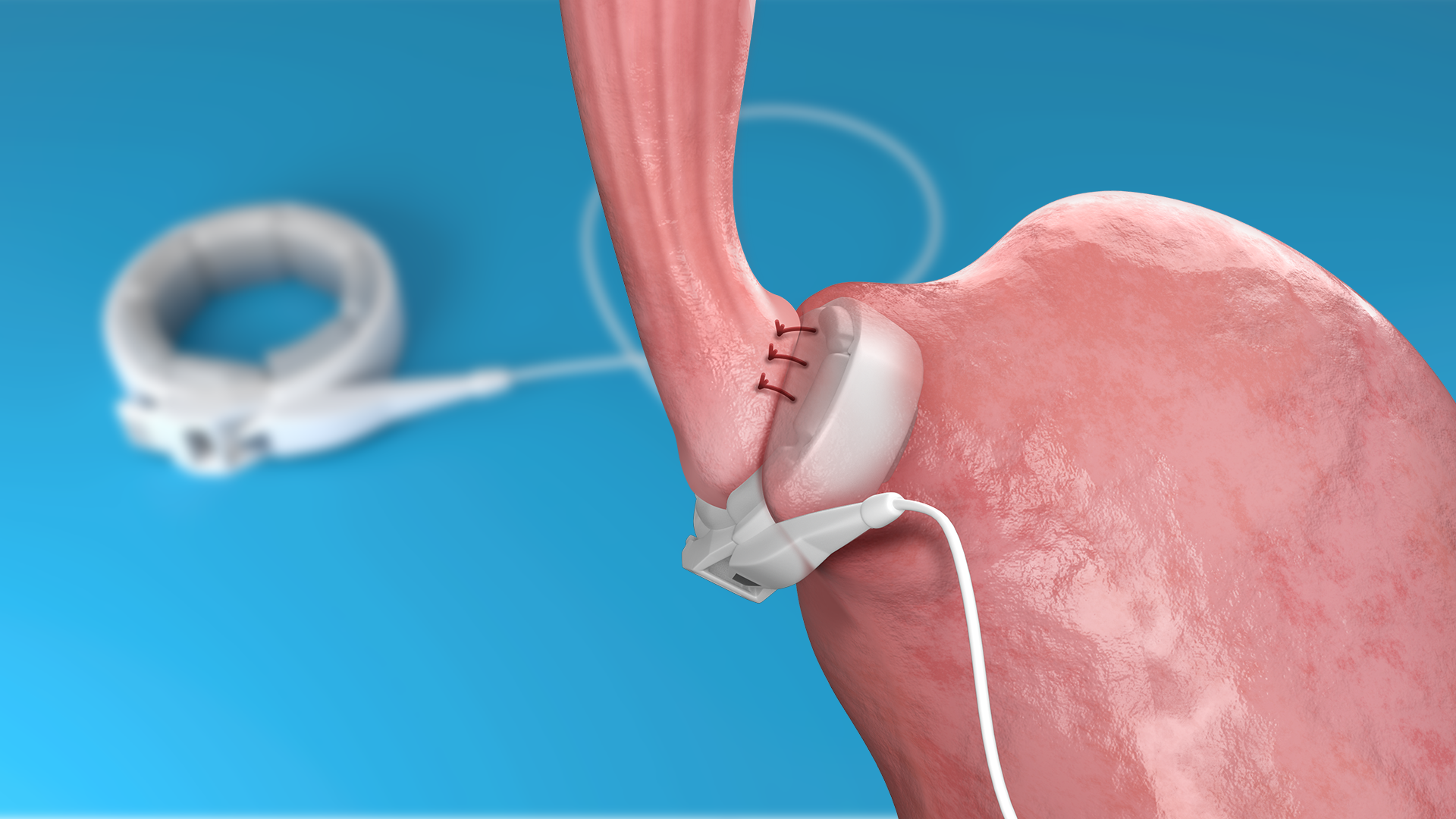

Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band

In this type of surgery, the surgeon places a ring with an inner inflatable band around the top of your stomach to create a small pouch. This makes you feel full after eating a small amount of food. The band has a circular balloon inside that is filled with salt solution. The surgeon can adjust the size of the opening from the pouch to the rest of your stomach by injecting or removing the solution through a small device called a port placed under your skin.

After surgery, you will need several follow-up visits to adjust the size of the band opening. If the band causes problems or is not helping you lose enough weight, the surgeon may remove it.The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of the gastric band for people with a BMI of 30 or more who also have at least one health problem linked to obesity, such as heart disease or diabetes.

Gastric Sleeve

Gastric Sleeve

In gastric sleeve surgery, also called vertical sleeve gastrectomy, a surgeon removes most of your stomach, leaving only a banana-shaped section that is closed with staples. Like gastric band surgery, this surgery reduces the amount of food that can fit in your stomach, making you feel full sooner. Taking out part of your stomach may also affect gut hormones or other factors such as gut bacteria that may affect appetite and metabolism. This type of surgery cannot be reversed because some of the stomach is permanently removed.

Gastric Bypass

Gastric bypass surgery, also called Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, has two parts. First, the surgeon staples your stomach, creating a small pouch in the upper section. The staples make your stomach much smaller, so you eat less and feel full sooner.

Next, the surgeon cuts your small intestine and attaches the lower part of it directly to the small stomach pouch. Food then bypasses most of the stomach and the upper part of your small intestine so your body absorbs fewer calories. The surgeon connects the bypassed section farther down to the lower part of the small intestine. This bypassed section is still attached to the main part of your stomach, so digestive juices can move from your stomach and the first part of your small intestine into the lower part of your small intestine. The bypass also changes gut hormones, gut bacteria, and other factors that may affect appetite and metabolism. Gastric bypass is difficult to reverse, although a surgeon may do it if medically necessary.

Duodenal Switch

This surgery, also called biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, is more complex than the others. The duodenal switch involves two separate surgeries. The first is similar to gastric sleeve surgery. The second surgery redirects food to bypass most of your small intestine. The surgeon also reattaches the bypassed section to the last part of the small intestine, allowing digestive juices to mix with food.

This type of surgery allows you to lose more weight than the other three. However, this surgery is also the most likely to cause surgery-related problems and a shortage of vitamins, minerals, and protein in your body. For these reasons, surgeons do not perform this surgery quite often.

This type of surgery allows you to lose more weight than the other three. However, this surgery is also the most likely to cause surgery-related problems and a shortage of vitamins, minerals, and protein in your body. For these reasons, surgeons do not perform this surgery quite often.

Most Common Weight-loss Surgeries is Gastric Band. In this the surgeon places an inflatable band around top part of stomach, creating a small pouch with an adjustable opening.

Pros

•Can be adjusted and reversed.

•Short hospital stay and low risk of surgery-related problems.

•No changes to intestines.

•Lowest chance of vitamin shortage.

Cons

•Less weight loss than other types of bariatric surgery.

•Frequent follow-up visits to adjust band; some people may not adapt to band.

•Possible future surgery to remove or replace a part or all of the band system.

Gastric Sleeve

There are two components to the procedure. First, a small stomach pouch, approximately one ounce or 30 milliliters in volume, is created by dividing the top of the stomach from the rest of the stomach. Next, the first portion of the small intestine is divided, and the bottom end of the divided small intestine is brought up and connected to the newly created small stomach pouch. The procedure is completed by connecting the top portion of the divided small intestine to the small intestine further down so that the stomach acids and digestive enzymes from the bypassed stomach and first portion of small intestine will eventually mix with the food.

The gastric bypass works by several mechanisms. First, similar to most bariatric procedures, the newly created stomach pouch is considerably smaller and facilitates significantly smaller meals, which translates into less calories consumed. Additionally, because there is less digestion of food by the smaller stomach pouch, and there is a segment of small intestine that would normally absorb calories as well as nutrients that no longer has food going through it, there is probably of some degree less absorption of calories and nutrients.

Most importantly, the rerouting of the food stream produces changes in gut hormones that promote satiety, suppress hunger, and reverse one of the primary mechanisms by which obesity induces type 2 diabetes.

(The author is Associate Professor, Department of Pulmonary, Critical care & Sleep Medicine, Vadhaman Mahavir Medical College & Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi)