Healers Under Attack

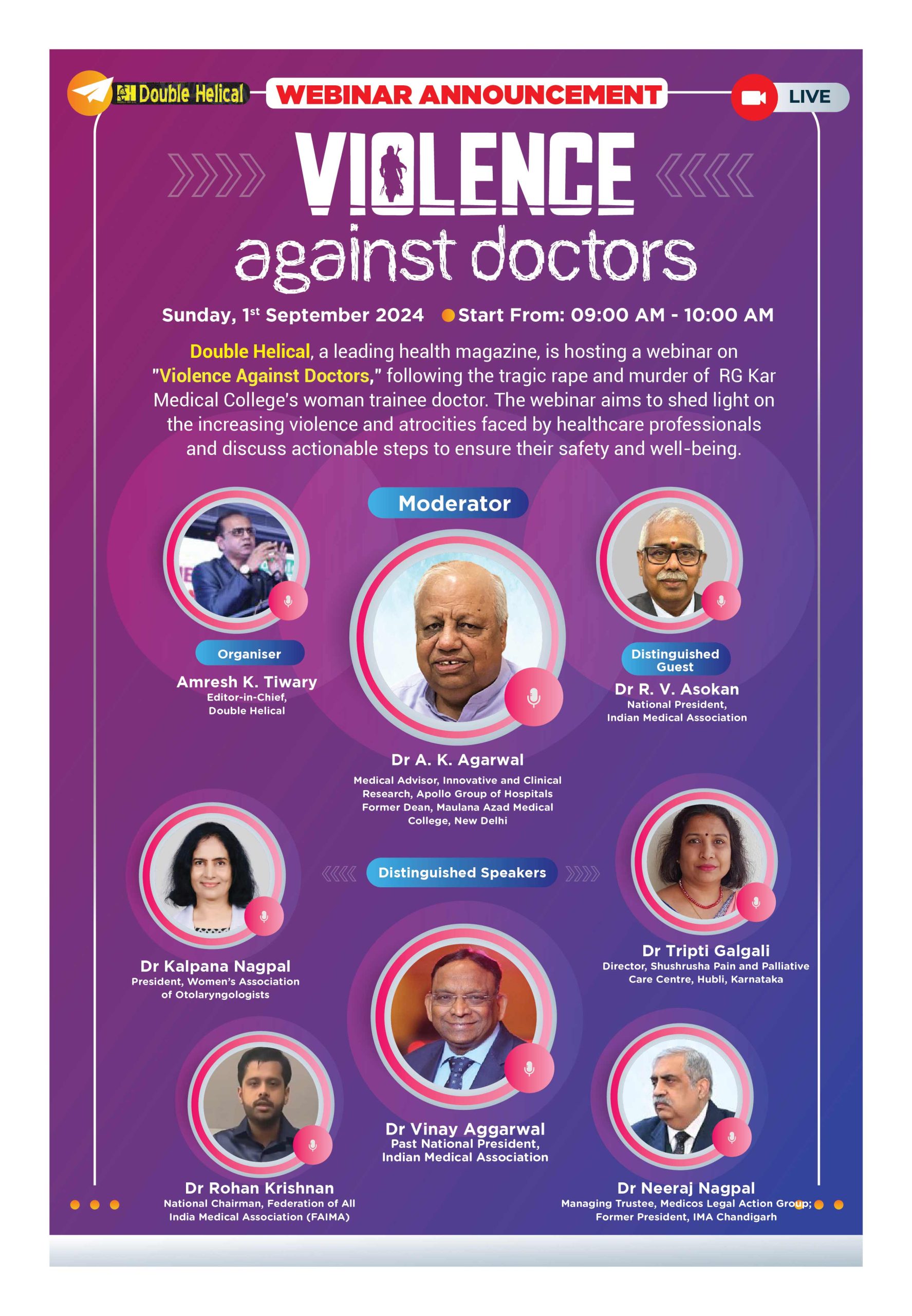

A highly insightful webinar, recently hosted by Double Helical, brought together prominent healthcare leaders to address the rising tide of violence against doctors, a crisis brought into sharp focus by the recent tragedy at RG Kar Medical College.

By DH News Bureau

With prominent voices like Dr R V Asokan, National President of the Indian Medical Association (IMA), leading the discussion, the webinar hosted by Double Helical, titled “Violence Against Doctors: A Call for Action,” highlighted the urgent need for legal protection, institutional reforms, and immediate action to safeguard medical professionals. It brought together eminent healthcare leaders to discuss the alarming rise in violence against medical professionals. Against the backdrop of recent tragedies, including the brutal incident at RG Kar Medical College, Kolkata, West Bengal, the discourse underlined the urgent need for unified laws and better security measures across healthcare institutions. Excerpts…

With prominent voices like Dr R V Asokan, National President of the Indian Medical Association (IMA), leading the discussion, the webinar hosted by Double Helical, titled “Violence Against Doctors: A Call for Action,” highlighted the urgent need for legal protection, institutional reforms, and immediate action to safeguard medical professionals. It brought together eminent healthcare leaders to discuss the alarming rise in violence against medical professionals. Against the backdrop of recent tragedies, including the brutal incident at RG Kar Medical College, Kolkata, West Bengal, the discourse underlined the urgent need for unified laws and better security measures across healthcare institutions. Excerpts…

Amresh K Tiwary: A warm welcome to today’s crucial webinar hosted by Double Helical, addressing a topic of utmost importance—Violence Against Doctors. Today’s gathering serves as a vital platform to analyse the rising incidents of violence and the severe challenges faced by our healthcare professionals, spotlighted by the recent tragedy at RG Kar Medical College.

I’d like to extend a heartfelt welcome to our distinguished Chief Guest, Dr RV Asokan, National President of the IMA, who has long been a staunch advocate for the medical community. We are also honoured to have with us an esteemed panel of speakers, each a respected voice in the healthcare field: Dr Vinay Aggarwal, Dr Neeraj Nagpal, Dr Kalpana Nagpal, and Dr Tripti Galgali.

Together, we will delve into the root causes of this alarming trend, discuss legal and institutional protections, and work towards viable solutions to ensure the safety and well-being of our medical community. Without further delay, I’d like to invite our esteemed moderator, Dr A K Agarwal, Advisor of Medical Research and Innovation at Apollo Hospitals and former Dean of Maulana Azad Medical College, to commence the discussion.

Dr A K Agarwal: Thank you, Tiwary Ji, and thanks to the Double Helical team for organising this vital event. This magazine has been covering diverse aspects of the medical profession, but today’s focus on violence against doctors addresses a particularly challenging and tragic issue. I have personally witnessed this growing menace since my days as a medical student in 1968, and the trend has only escalated. The recent horrifying incident in Kolkata is something none of us could have imagined—a young doctor’s life taken in a most barbaric manner.

The medical profession, it seems, has become a soft target for this kind of violence. With us today is a galaxy of panellists, as introduced by Tiwary Ji, and I am especially grateful for the presence of Dr Asokan, IMA President. Dr Asokan, your leadership during these trying times has been invaluable, and we are eager to hear your thoughts on this issue.

Dr R V Asokan: Thank you, Dr Agarwal, and my sincere thanks to the Double Helical team for creating this platform to discuss such an important issue. Unfortunately, violence against doctors has plagued us for over three decades. The root cause, more often than not, is a mismatch between patient expectations and outcomes, coupled with the high cost of care. This issue is further exacerbated by the government’s inadequate investment in healthcare—currently just 1.1 per cent of the GDP.

Private sector hospitals, be they large corporate setups or smaller primary care facilities, are also not spared from violence, and it has manifested in different ways—arguments over bills, lack of communication, or grief over sudden deaths. However, the incident in Kolkata represents an unprecedented level of bestiality, with a doctor brutally murdered within hospital premises.

The Supreme Court has recently taken up two crucial aspects related to this: safety and security in hospitals, and the working conditions of resident doctors. The young doctor in Kolkata was on duty for 36 hours straight, with no proper place to rest, which highlights the need for immediate reforms in working conditions. The IMA has long advocated for a Central Act that would ensure uniform safety standards and legal protections for medical professionals across all states. This Act would serve as a deterrent against violence, just as the POCSO Act did for child sexual abuse cases. We believe nothing short of such a central law will suffice.

Thank you again to Double Helical for bringing us together to discuss these crucial issues.

Dr AK Agarwal: Thank you, Dr Asokan. Your leadership and the Supreme Court’s involvement have indeed started the conversation, but much more remains to be done. Let’s continue this dialogue. I now invite Dr Vinay Aggarwal, past National President of the IMA, to share his insights. Dr Aggarwal has been an active member of the IMA for decades, and I’ve always admired the energy and dedication he brings to every cause.

Dr Vinay Aggarwal: Thank you, Dr Agarwal, and my heartfelt thanks to Dr Asokan and Amresh Ji for organising this highly significant webinar. As Dr Asokan rightly said, violence against doctors has been an unfortunate reality for the last three to four decades, with incidents evolving in both scale and intensity over the years.

I’d like to begin by citing a few recent examples. About seven years ago, in Tuticorin Tamil Nadu, a gynaecologist was brutally killed by the husband of one of her patients. Then, there was the tragic case of Dr Archana Sharma in Dausa, Rajasthan, who was driven to suicide after being harassed by patient relatives and local authorities. Dr Vandana in Kerala was killed by a patient’s attendant, and more recently, the heinous incident in Kolkata where a young doctor was raped and murdered within hospital premises.

What we are seeing today is an acute gap between the public’s expectations and the realities of healthcare delivery. When I first started my practice in the 1980s, such violence was unheard of, despite seeing over 250 patients a day. Fast forward to today, and we are faced with an alarming increase in incidents of verbal abuse, manhandling, and even murder. Rising healthcare costs, lack of communication, and a general lack of unity within the medical profession are all contributing factors.

To address this issue, I believe three major steps need to be taken: improving working conditions, enhancing hospital security, and introducing a stringent, central law across all states to deal with incidents of violence against doctors. Currently, 25 states have their own laws, but these vary widely in terms of penalties and enforcement, which is not enough to act as a deterrent.

Dr A K Agarwal: Thank you, Dr. Vinay, for sharing your very valuable experience. Now, my next panellist is Dr Neeraj Nagpal, Managing Trustee at the Medicos Legal Action Group and former President of the IMA, Chandigarh. He is actively involved in medical issues, particularly in the field of medical negligence.

Dr Neeraj Nagpal: Thank you, sir, for this opportunity, and my regards to all my seniors here. However, I’m going to be a bit blunt. Whenever we talk about violence against doctors, I do not like the term “introspection” being associated with it. Violence against doctors should be condemned at all levels—there is no justification for it. Communication errors, documentation issues, or cost problems are not the reasons for violence. The reason for violence is the absence of deterrence. We do not create strong enough deterrents to prevent the next instance of violence.

We are talking about 25 state laws. When I go to the police to file a complaint about violence at a nursing home, the police don’t know the state laws; they only talk about the IPC or, now, maybe the BNS. This is one reason state laws are ineffective.

Another argument made is that we cannot have a profession-specific act, but we have already seen exceptions, like in the DK Gandhi judgment of the Supreme Court, which stated that the legal profession is different from others. Similarly, I argue that medicine is also different because the services we provide are a fundamental right of the public. The government is supposed to provide these services, but since it doesn’t, the private sector steps in. Our services are essentially fulfilling the public’s fundamental right to healthcare, as recognised by multiple Supreme Court judgments under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act 2013, made after the Nirbhaya case, was created to address specific issues like rape and acid attacks, even though IPC sections already existed. Similarly, Dr Asokan pointed out why a Central law is necessary. We have seen the enactment of the Transplantation of Human Organs Act and the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, among others, because the IPC was not capable of handling these specific crimes. This is why we need a Central Act to deal with violence against doctors.

The incident at RG Kar Medical College in West Bengal is a classic example of why a central act is needed. State acts are ineffective when not properly implemented, and the Centre cannot enforce a state law, and even the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) will only be applicable five years from now in some states.

Violence against doctors is not the same as violence against other professionals or citizens. In a hospital, when violence erupts, it affects not just the doctors but also the patients who are innocent bystanders. In PGI, for instance, there was an incident where one patient party started attacking doctors in the emergency room, diverting the attention of all medical staff, which led to the death of another critically ill patient. This resulted in a consumer case against the hospital. Who is responsible for that patient’s death?

This is why violence against doctors is different. It has far-reaching consequences, and there is no justification for it. Incidents like the one in Assam, where a doctor was lynched in a tea garden, deter hundreds of doctors from going to rural or difficult areas to serve. This is why we need a Central Act to ensure proper security and safety measures.

Moreover, it’s not enough just to have a Central Act; the provisions of that Act are equally important. If institutions like RG Kar fail to ensure the safety of their residents, the National Medical Commission (NMC) should derecognise them for postgraduate admissions until a reinspection proves that adequate safety measures have been put in place. I think I’ll stop here before I go on too long. Thank you.

Dr A K Agarwal: Thank you for sharing your insights and experiences. I fully agree that a Central Act is needed. Let me share an example with all the esteemed panellists, particularly the IMA President. In 2007, the Supreme Court addressed the issue of ragging in educational institutions across India and created the Raghavan Committee. I was fortunate to be a member of that committee. The recommendations we made after consulting stakeholders across the country were accepted, and an anti-ragging law was passed. While it may not be 100 per cent effective, ragging has decreased by at least 90 per cent, and there is now a real fear of the law among students, faculty, and heads of institutions. This is the kind of impact we need to create with a law against violence against doctors.

Now, our next speaker is Dr Kalpana Nagpal, a dynamic ENT surgeon, the first woman robotic surgeon at Apollo, New Delhi, and President of the Women’s Association of Otolaryngologists, where she leads more than 1,000 women ENT surgeons across India. Welcome, Dr Kalpana.

Dr Kalpana Nagpal: Thank you, Dr Agarwal, and thank you for your kind blessings. I’m pleased to share that we now have more than 2,000 members in the Women’s Association of Otolaryngologists.

On behalf of the association, we strongly condemn the RG Kar case and demand complete justice, including prosecuting all those guilty. We have already filed a PIL in the Supreme Court.

Regarding safety for doctors, I fully agree with Dr Neeraj Nagpal that we need a central law. Here are three suggestions for ensuring the future safety of doctors:

1. Doctors should carry alarm badges with robust alarm systems. The alarm should be connected to the police and the hospital management so that help can be summoned immediately, even before a mob attack begins.

2. Institutions must take responsibility for ensuring security. Hospital management should be accountable for preventing such incidents.

3. Mobile phones should be banned in critical areas like ICUs and operation theatres. Phones are often used to coordinate attacks, as likely happened in the RG Kar case.

Additionally, there should be no delay between the assault and filing a complaint. Robust systems need to be in place, including alarm systems, security personnel, and police coordination. Strong laws must be enforced, with severe penalties for any lapses in security, such as malfunctioning CCTV cameras.

We are dealing with people who may have personality disorders or criminal tendencies, and security protocols must be strict. The heinous crime at RG Kar has left everyone devastated, and we must ensure that such atrocities never happen again. I request the IMA President to take up this issue at the appropriate level and ensure that justice is served. I would be truly grateful. Thank you all for this platform.

Dr A K Agarwal: Thank you, Kalpana, for sharing your thoughts, which reflect the resurgence of women in our country. I can see that Dr Chanchal, General Secretary, is also present among us, and in fact, I would like to invite her to say a few words. Dr Chanchal, could you please speak for a minute? We are running short on time.

Dr Chanchal: Thank you, sir, and Dr Kalpana. I think most of the points have already been well made. Dr Kalpana addressed the emotional aspect, and I still have tears in my eyes thinking about that particular girl and what she must have gone through. I think we should make a vow here today that nothing of this sort will happen to any girl in our country again. And, sir, I would request you, given your high position, to ensure that discussions are followed by action. We need a clear action plan with the police and lawmakers, and we must make sure that this issue doesn’t end with just protests or words. We are all emotionally involved right now, but over time, these things tend to fade, as we saw with the Nirbhaya case. We must not allow this to die down. We have been protesting every day. Just yesterday, we held a protest in front of Apollo Hospital, along with women from the local community. Unfortunately, even our peaceful candle march was stopped, though Section 144 was not in place. Despite this, the police came and stopped us from standing with candles. Dr Neeraj, as a legal expert, please enlighten us on how they can stop peaceful protests by women and doctors. This infringement on our constitutional rights must be addressed.

Dr A K Agarwal: I agree with Dr Chanchal that we must take strong initiatives, and we are nearing the conclusion of certain important steps, which will be summarised later. But first, our final speaker, Dr Tripti Galgali, Director of Shushrusha Pain and Palliative Care Centre in Karnataka, will share her thoughts. I understand that she is very passionate about this subject, besides her own expertise in her field. Dr Tripti, may I request you to speak?

Dr Tripti Galgali: Good morning, everyone. I am an anaesthesiologist practicing in Hubli, Karnataka, and I also blog regularly. All the esteemed speakers have covered most of the points, but I would like to add that the attitude of lawmakers is crucial. Let me cite an example: about five or six years ago, our Paediatrics Department head at a government hospital here was slapped in front of the entire hospital by the local MLA, Mr Vinay Kulkarni. Although doctors protested, no action was taken against him. This highlights a sad reality—lawmakers behave brutally towards doctors just to showcase their power. Another incident involved Labour Minister and Dharwad district in-charge Santosh Lad, who reprimanded the head of the district hospital in front of staff, patients, and the public, and it was broadcast on local television. When lawmakers exhibit such behaviour, it sets a poor example and encourages the public to act similarly. Therefore, we must address the attitudes of lawmakers, the police, and even lawyers. We have seen many cases of medical negligence brought against doctors, and the attitude of lawyers towards us has often been unfavourable. Unless we address these three groups, how can we expect to educate the public?

Dr A K Agarwal: Thank you, Dr Tripti, for sharing your views and the examples you provided. It’s disheartening to hear that such incidents happen, even involving lawmakers. A change in the mindset of not just the general public but also responsible citizens, including politicians and bureaucrats, is crucial.

Dr Neeraj: I understood the point raised regarding politicians. We have faced similar issues, and I can give you multiple examples. In one case, the Vice Chancellor of a Health University was forced to lie on a dirty bed by a local MLA. He later resigned due to public pressure, but the point remains that it’s often failed or wannabe politicians who organise mobs. In India, we face a type of violence unique to South Asia—mob violence. How do these mobs, comprising 200 people, gather if not through organised telecommunication? Many of these are professional protesters, seen in election rallies or when a leader visits. These groups are often linked to caste, religious, or political subgroups. This is why political parties hesitate to support stringent laws against violence, as 90 per cent of those prosecuted would be connected to one political party or another. This is our biggest challenge. While we need strong laws, we also need the determination to prosecute offenders. I have been involved in filing complaints for 30 to 40 incidents, but in almost all cases, the doctors eventually withdraw their complaints due to threats, blackmail, or cross FIRs alleging criminal negligence. Even in Karnataka, there was an incident where a Member of Parliament slapped a department head. The real danger comes from wannabe politicians who slap doctors, create a scene, and then make headlines. This gives them visibility, which they leverage in future elections. Therefore, we not only need stronger laws but also the conviction to enforce them. If anyone is afraid of facing a criminal negligence case, they can approach me, and I will guide them on how to fight it.

Dr A K Agarwal: Drafting a Central Act, I believe, is crucial.

Dr Neeraj: The draft has already been shared in the public domain. It is with the IMA headquarters. I believe Dr Vinay is also aware of it. We’ve included strict provisions in the draft, such as revoking all central government accreditations and approvals for hospitals where grievous injury or death of a doctor occurs during violence, until a reinspection deems the hospital safe for both patients and doctors. It is essential that our own community understands that such violence is unacceptable. If the head of a department tells a resident to “introspect,” how can we expect that resident to file an FIR? It should be the responsibility of the head of the department or institution to file the FIR, and if they fail to do so, they should face six months’ imprisonment. This is part of the draft I have already shared.

Dr B N Gupta: Thank you, Dr Neeraj, for presenting your views. I am President of the IMA Branch in Jharkhand. While many points have been well-covered, I would like to emphasise a few more. As an ophthalmologist with hospitals in Dhanbad and Delhi, we don’t often deal with death-related cases, but we do face rough situations from time to time. From my perspective, we must avoid making tall claims to patients and always explain the prognosis sincerely. This helps in maintaining good rapport. Secondly, our staff and doctors need to stand firm on their points and avoid being defensive, which I believe contributes to some of these circumstances. Thank you.

Dr A K Agarwal: No doubt, Dr Gupta. Communication is crucial, and proper documentation is equally important. I now request Dr Vinay to summarise the discussion.

Dr Vinay Agarwal: Thank you, Dr Agarwal. A lot of excellent points have been raised, and Dr Neeraj and Dr Kalpana have been particularly clear and insightful. I would like to add that, like the recently introduced BNS Act, we should ensure that these cases are tried on a fast-track basis. Justice delayed is justice denied. I’ll take a minute to share an example. In 1993, when I was President, a doctor was beaten up by a Member of Parliament, M C Sharma, and another MP, Anand Agarwal. It was with great difficulty that we managed to file a case. However, it saddens me to say that the trial court delivered a verdict in 2022—29 years later! Anand Agarwal was sentenced to six months in prison, but he was granted another month to appeal. This underscores the importance of speedy trials. Associations should play a crucial role in supporting victims, their families, and the institutions. By creating enough pressure, we can ensure fast-track trials for such cases, and the law itself should include provisions for this.

Dr A K Agarwal: Thank you very much, Dr Vinay . We cannot afford to have another heinous incident like the one in Kolkata. Otherwise, our younger doctors and the profession itself will break down. With that, I would like to thank all the panellists and the Double Helical team, led by Tiwary Ji, for organising this seminar. Please reach out to Double Helical if you have any thoughts or suggestions for future discussions.