Mothers for Hire

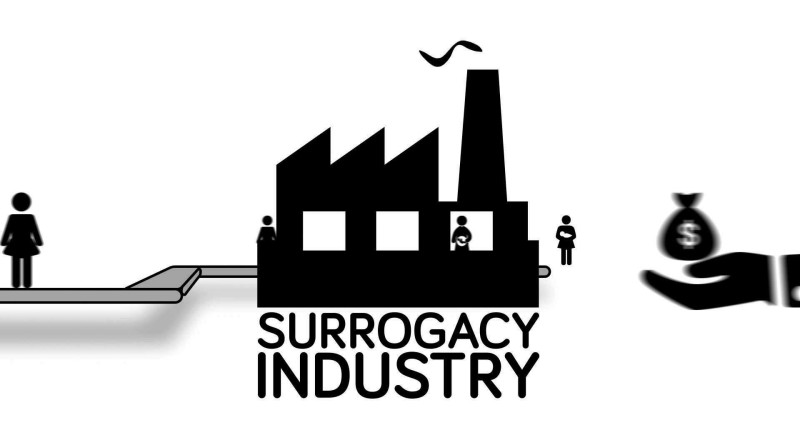

The proposed draft Surrogacy Bill 2016 seeks to address the need for legislation to regulate surrogacy that has taken proliferated as a ruthless trade on a large-scale

By Vishal Duggal

The Union Cabinet recently cleared the draft bill called Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Bill which is likely to be introduced in the Parliament in the winter session. If passed, the Act will deal a death blow to the estimated $2 billion industry that has made the country a global surrogacy hub.

The draft bill, proposed by NDA led government, prohibits commercial surrogacy, like in the UK, while permitting altruistic surrogacy. It proposes to now allow only heterosexual childless couples, married for at least five years, to have children through surrogate mothers, who have to be close relatives, and without the involvement of a financial transaction. It also lays down that only mothers with at least one child can offer to rent out their wombs, and may do so only once in their lifetime.

The banning of commercial surrogacy can perhaps open up doors for adoption as well. In a country like India, where one encounters frequent stories of children being abandoned by their parents out of poverty or social stigma, especially girls, banning commercial surrogacy could encourage parents to look toward adoption as a means of fulfilling their dreams of parenthood.

According to Union Health Minister JP Nadda, a family institution is required to protect children from potential abuse and the adoption laws, too, need many changes that will be taken up later on. External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj has suggested that couples who don’t have close relatives who can offer to be surrogate mothers should look at adoption more closely. As far as surrogates are concerned, the government’s heart might be in the right place in wanting to curb the exploitation of poor women hired to bear children for others. Not that the government wants to completely ban the renting of wombs, but it wants to make it an altruistic practice, where eligible women offer to be surrogates for family members in need. The bill says surrogate mothers should be married and should have given birth to a healthy child before.

The draft bill provides for surrogacy as an option to parents who have been married for five years can’t naturally have children, lack access to other reproductive technologies, want biological children and can find a willing participant among their relatives. This would come as a major blow to fertility clinics in India, as most of them have thriving commercial surrogacy practices, which would be outlawed under the current form of the bill. Commercial surrogacy will result in 10 years’ imprisonment.

The bill also seeks to clarify the legal position of such a child and ensures that a child born of surrogacy will have all legal rights as a citizen. It would also restrict overseas Indians, foreigners, unmarried couples, homosexuals, and live-in couples from entering into a surrogacy arrangement. The surrogate mother has to be a married woman who has herself borne a child and is neither a non-resident Indian (NRI) nor a foreigner. Couples who already have biological or adopted children cannot commission a surrogate child.

As expected, the bill has generated a lot of debate around the country. Opponents have argued that by allowing surrogacy for select classes of citizens on the basis of their lifestyle, sexual orientation, and life choices, the bill would violate citizens’ Fundamental Rights as laid down in Article 14 of the Indian Constitution.

However, the bill seeks to be in step with the legal issues at the moment. Gay rights are still an evolving issue in India. While the Supreme Court is sitting on a review petition on Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, pertaining to the status of gay rights, no clear legal stand on the issue has emerged. Hence at this point, conferring legal rights to a surrogate child to gay parents would endanger the rights of the child itself.

The Surrogacy (Regulation) bill can clarify the rights for India’s gay population only once these larger legal questions (about the status of gay marriage, for instance) have been answered. Hence at this point, restricting surrogacy to relationships which have a clear standing in the eyes of law protects the rights of the child and ensures consonance with Article 14 of the Indian Constitution rather than doing disservice to it.

The second major issue relates to the question of disallowing commercial surrogacy and restricting foreigners from availing themselves of surrogacy in India. Since the inception of commercial surrogacy, a number of incidents have sparked unpleasant legal questions surrounding commercial surrogacy involving foreigners. In 2012, for example, an Australian couple who had twins by surrogacy arbitrarily rejected one while selecting the other. Such issues reveal the complexities that surround commercial surrogacy.

While commercial surrogacy has been practiced in India legally since 2002, the large-scale proliferation of the trade has so far gone on unchecked in the absence of any legislation. It is one of the very few countries—Russia, Ukraine, and some U.S. states are among others—where commercial surrogacy is practised (Thailand, a formerly booming center for the procedure, banned commercial surrogacy last year). According to estimates by a UN-backed study of July 2012, the industry is worth more than $400 million a year, with over 3,000 fertility clinics across India.

The need for legislation to regulate surrogacy has been long felt amid ethical and legal concerns. After a survey of 100 surrogate mothers in Delhi and Mumbai, the Center for Social Research published in a report concluding that there were few safeguards in terms of legal provisions or health insurance for the women, who were mostly poor and uneducated. There was no fixed rule for payments nor was there any provision for post-pregnancy healthcare.

With no law to regulate Indian surrogacy as things stand, a profitable surrogacy market has sprung up. Clinics rely on Indian contract law to draw up binding agreements between surrogates and intended parents, and registrars facilitate naming intended parents on Indian birth certificates. All together, it adds up to an affordable but unregulated way of having a child for infertile and gay couples.